Perhaps like the Q document of conference talks with guidelines of how often it may be referenced for General Conference. There is probably a similar Deseret News guideline on articles appearing in their religion section. Those submitting articles for the Deseret News get paid by the column inch, but the editors probably do no wish to pay for the identical story unless several years have passed.MrStakhanovite wrote: ↑Mon Oct 05, 2020 11:06 amI wonder if there is some kind of “Q” document Daniel has on his computer where he keeps all these samples of text organized by topic, then he just copies and pastes when the time comes to say something on his blog.

Tales From The Reverend?????s Office: Why Won?????t Daniel Peterson STFU?

-

_moksha

- _Emeritus

- Posts: 22508

- Joined: Fri Oct 27, 2006 8:42 pm

Re: Tales From The Reverend’s Office: Why Won’t Daniel Peterson STFU?

Cry Heaven and let loose the Penguins of Peace

-

_Physics Guy

- _Emeritus

- Posts: 1331

- Joined: Sun Aug 28, 2016 10:38 pm

Re: Tales From The Reverend’s Office: Why Won’t Daniel Peterson STFU?

Just to be sure, which kind of Q material we be talkin’ ’bout here? :confused:

-

_moksha

- _Emeritus

- Posts: 22508

- Joined: Fri Oct 27, 2006 8:42 pm

Re: Tales From The Reverend’s Office: Why Won’t Daniel Peterson STFU?

The source material for that LGBTQ acceptance group which is not yet out of the closet: QAnon.Physics Guy wrote: ↑Tue Oct 06, 2020 7:31 pmJust to be sure, which kind of Q material we be talkin’ ’bout here? :confused:

Here is a good LDS support question for Dr. Peterson to ask Gemli. "How is it that the cavemen survived the asteroid, but the dinosaur didn't?" Later on the SeN crowd will spring the answer that the dinosaurs lacked the gospel on an unsuspecting Gemli.

Cry Heaven and let loose the Penguins of Peace

-

_Physics Guy

- _Emeritus

- Posts: 1331

- Joined: Sun Aug 28, 2016 10:38 pm

Re: Tales From The Reverend’s Office: Why Won’t Daniel Peterson STFU?

Of course. All Q's are the same. Q is an uncommon letter, after all. What are the chances that it would really appear independently in so many places just by chance? About as low as the chances that Joseph Smith would guess that the Mayans made roads, that's how low.

If people don't realize that the dinosaurs were killed by the Knights Templar then they have a lot of reading to do. I'm not going to spoon-feed them.

If people don't realize that the dinosaurs were killed by the Knights Templar then they have a lot of reading to do. I'm not going to spoon-feed them.

-

_MrStakhanovite

- _Emeritus

- Posts: 5269

- Joined: Tue Apr 20, 2010 3:32 am

Re: Tales From The Reverend’s Office: Why Won’t Daniel Peterson STFU?

Part 2(g): Epistle to The North African

Now to really drive home what both Gadamer and Popper said about induction, it’ll be helpful to return to Daniel Peterson and the provocative glimpse he gave us into the future pièces de résistance of his Mopogetic career: The multi volume set of ‘The Reasonable Leap into Light’. Recall in ‘The Reasonable Leap into Light: A Barebones Secular Argument for the Gospel’ describes the entire project as a kind of meta-argument that intends to be a robust philosophical justification for the Mormon worldview that proceeds systematically and incrementally from a rather “secular” basis:

It begins right there in the working title (i.e. “Reasonable Leap”) and I think the title itself is an homage to William Lane Craig’s book ‘Reasonable Faith: Christian Truth and Apologetics’. The book operates as a kind of a master class on Evangelical apologetics by way of presenting the issue of Evangelism in the light of systematic theology. The popularity of ‘Reasonable Faith’ has grown to such an extent that the book has pretty much become one of the standard works of Apologetics in the Evangelical world, often assigned at the undergraduate and graduate level courses in various Bible colleges and seminaries around the English speaking world.

Daniel consumes a steady diet of Christian Apologetics and is an obvious admirer of Craig; I often speculate that Daniel likes to think of himself as the William Lane Craig of Mormonism and I’m confident he has envisioned the posthumous publication of ‘The Reasonable Leap into Light’ as being celebrated enthusiastically by Mormons and eventually becoming a “standard reading” at BYU. So it shouldn’t be surprising then that Daniel follows the Evangelicals in framing the apologetic goal as not establishing the uncontested truth of Christianity (or Mormonism in Daniel’s case), but to demonstrate that those who affirm Christianity (or Mormonism) do so rationally as fallible beings:

To help demonstrate this kind of rationality as game theory approach and its value, Daniel introduces his audience to the now infamous Bayes’ theorem of probability. To be perfectly frank about this, I don’t think Daniel was introduced to Bayes’ theorem during the course of his “studies” into either the natural sciences, economics, or philosophy. Rather I’d assert that he was introduced to it via William Lane Craig during a debate with Bart Ehrman about the historical reliability of the New Testament.

I have a copy of Bart Ehrman’s introduction to the New Testament (3rd edition) where he makes a claim to the effect that a practicing Historian of today seeks to establish what “probably” happened in the past and that since supernatural miracles are by definition (according to Ehrman) the least probable of all events, it follows that Historians can’t establish a miracle (i.e. Jesus rising from the dead) as being the most probable course of events. Bart more or less rehearsed this line of reasoning during the debate with Craig.

It was in effect a slow pitch that allowed Craig to smash right out of the park in terms of rebuttal. Craig was able to frame his rebuttal as “Bart’s Blunder” and demonstrate handily that in a Bayesian framework, posterior evidence can be so unique and confirming that it can override any prior epistemic value that is less than 1. Within Bayesian terms, Craig’s point was simply a mathematical inevitability of the algebra involved.

Suffice to say Bart didn’t really have an answer to “Bart’s Blunder” simply due to the fact that was his first time ever encountering Bayes Theorem. I imagine it was Daniel’s first time as well and I bet he was fascinated by the encounter and immediately inuitied how he could use this for his own work:

I only know that Charles G. Werner existed because he edited a small anthology called ‘Inductive Logic’ I found in a used bookstore in Salt Lake City oddly enough in 2010. It is a cheap paperback published in 1973 by Kendall Hunt publishing company out of Dubuque Iowa. The publishing company is still in business in Dubuque today and it looks like they are still offering the same services they did to Charles Werner, the ability to print and publish custom books cheaply (relatively) for use in the classroom. Outside of this ugly green paperback, the only other words of Werner I’ve laid eyes on comes from a short article he wrote in 1977 for the ‘Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic’.

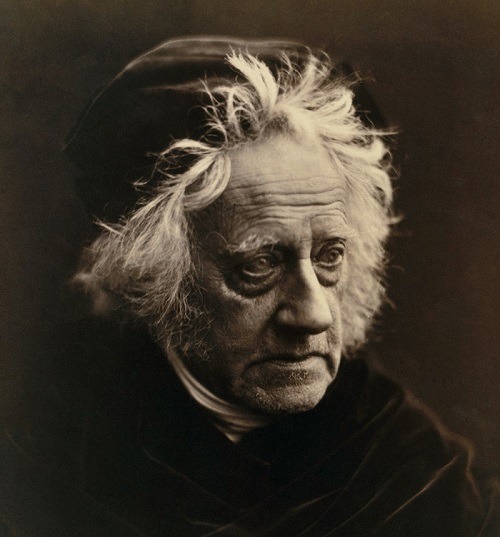

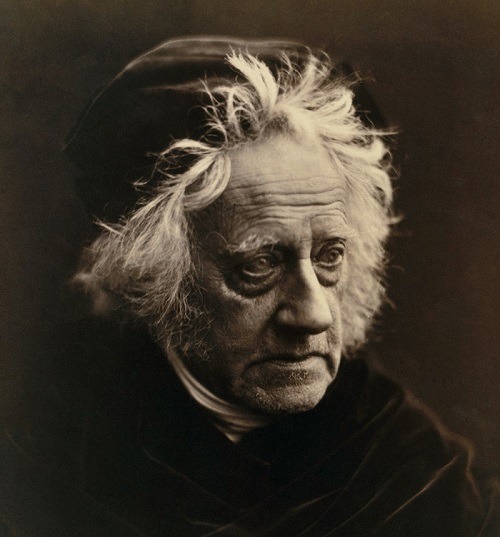

I always buy these kinds of books when I stumble across them, because I know they were created to serve a certain pedagogical purpose at a certain place at a certain time that simply no longer exists for us. The book has readings from the usual suspects on the topic such as William Whewell, John Stuart Mill, and C.S. Peirce, but also contemporaries like Bertrand Russell and Rudolf Carnap of the Vienna Circle, both of whom had just passed away three years prior to the publication of this little booklet. I wonder if Werner personally knew Carnap when he was at UCLA (Daniel’s alma mater!). Werner also included figures previously unknown to me, such as the English economist W. Stanley Jevons and J.F.W. Herschel. I noticed in Jevons’ Wikipedia entry that under the ‘Legacy’ header there is a quote from ‘The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy and Philosophers’ stating: "Jevons's general view of induction has received a powerful and original formulation in the work of a modern-day philosopher, Professor K. R. Popper." (LOL!) while Herschel originated the use of the Julian day in astronomy and invented blueprints!?! Wikipedia has an absolutely fantastic photographic portrait of Sir Herschel:

My God, Blixa. I’m just rambling to you now. I wrote three paragraphs about some obscure philosopher and embedded a picture from Wikipedia. I’m starting to write like how Daniel Peterson blogs! By the beard of Joseph F. Smith, what is next? Posting clickbait articles from ScienceAlert.com while plagiarizing Robert J. Hutchinson for my cracker barrel column in the Deseret News?! See you were wrong Blessed Blixa, visiting Reverend Kishkumen wouldn’t just do me some good, I actually think I might be in dire need of his ministrations. I need to continue.

So Werner (following C.S. Peirce) divides logical inferences into two broad categories: Deductive and Inductive. He indicates that Deduction can be characterized as “Explicative/Analytic” and Induction can be characterized as “Amplifiative/Synthetic”. Werner then defines those terms as follows (bolding mine):

So Daniel is working on a book length inductive argument laying out a positive case for his deeply held beliefs, that isn’t any different in principle from what Richard Swinburne did in his book ‘The Existence of God’. Why give this good man and scholar all this guff and libel and not hand the same treatment to Swinburne? I suppose I would if Swinburne had written the things Daniel has written. The real difference is that Swinburne is actually a competent philosopher with numerous contributions to the Philosophy of Science, so if I can pretend that Daniel has expended any meaningful effort reading any sort of philosophy text then I can easily assume the same about Richard without a nanosecond of hesitation.

What are some of those things Daniel has written? Once again I take us back to review ‘Can the Study of History Yield Genuine Knowledge’. I know I’ve quoted it before, but I see no harm in quoting it again. I see no problem going back to the same well again and again to make my points. Repetition is not a sign sloth.

Anyways Daniel says:

Yet my bulwark might still fail and a Mopologist reading this might object to my sources and reject my assertions that Gadamer would agree with them. Could I demonstrate that Gadamer believed similarly to my sources from the text of ‘Truth and Method’? Sure and I’ll do you one better. I’ll do it only using the section we’ve covered in this email. Consider the opening paragraph of ‘Truth and Method’ where Gadamer begins to establish the influence of John Stuart Mill:

Did John Stuart Mill understand induction as only being the activity of generating universal statements based on a certain number of particular statements? Thankfully for me, Werner’s ‘Inductive Logic’ includes the relevant passages from Mill’s ‘A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive’:

Just consulting the books that just happen to be within my reach, dearest Blixa, I can find numerous counterexamples to this. I can think of no less a historian than E.G. Turner himself, the revered papyrologist and master classicist, and his delightful tome ‘Greek Manuscripts of the Ancient World’:

Daniel grasps the basics of Gadamer’s point: the natural sciences and the humanities are different. From there he stumbles into a mistake about what Gadamer was writing about, the natural sciences and the humanities are not different because the natural sciences only seek to establish regularities and historians don’t, nor are they different because the natural sciences use induction and the humanities don’t. In actuality, the natural sciences and humanities differ because one uses methods and ought to and the other uses methods and ought not to.

Look at this disaster of an e-mail Blixa, see how the study of Mopologetics is often like the study of an onion? You consistently have to peel away layer after layer of mistakes as if there was no termination of layers, but the mistakes are just hideously stupid and made out of a careless disregard for any notion of honesty or care for a broader truth. Peel away at the onion of Mopologetics long enough Blixa and soon you will find yourself weeping.

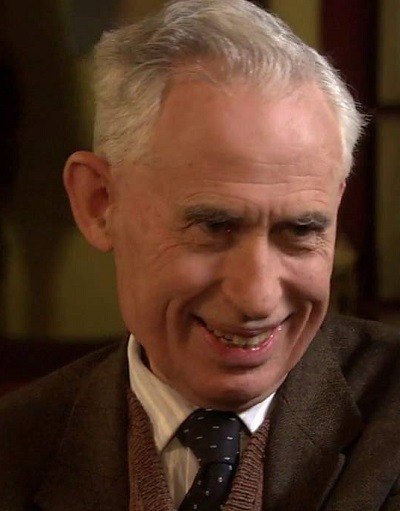

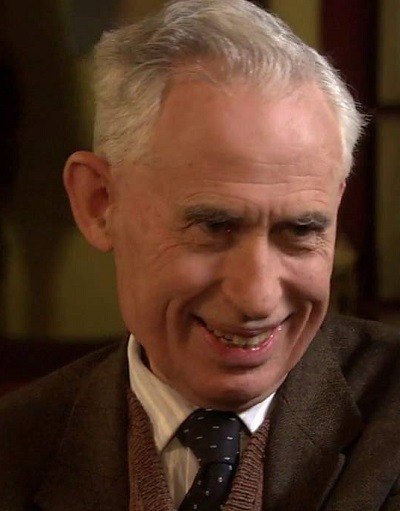

Since I mentioned Richard Swinburne, does this unflattering photo of him not scream Religious Education at BYU?

Now to really drive home what both Gadamer and Popper said about induction, it’ll be helpful to return to Daniel Peterson and the provocative glimpse he gave us into the future pièces de résistance of his Mopogetic career: The multi volume set of ‘The Reasonable Leap into Light’. Recall in ‘The Reasonable Leap into Light: A Barebones Secular Argument for the Gospel’ describes the entire project as a kind of meta-argument that intends to be a robust philosophical justification for the Mormon worldview that proceeds systematically and incrementally from a rather “secular” basis:

I quoted the paragraph in full because I think it is important to keep in mind that Daniel is just speaking in generalities about his project and even though he is just going to talk through an outline that is ultimately tentative, there are aspects about the work in progress that seem essential to the project. Daniel has a habit of giving remarkably bad takes on philosophers, but those bad takes are usually incidental and can be attributed to Daniel’s lack of discipline regarding texts, they can be removed and corrected without threatening the framework of ‘The Reasonable Leap into Light’. That framework is a notion of rationality predicated on probability.Daniel Peterson wrote:What do I mean by a secular argument? I mean an argument that’s not going to call upon things like the Spirit, the witness, the testimony of the Holy Ghost. That is a different thing, but that can’t be delivered to you by a lecture or by reading a book by itself. You have to get that yourself from God, that’s personal and individual to you. What I want to argue, though, is that there are arguments that can be made for the rationality of the Gospel, of belief in God, in Christianity and in specifically Mormonism. So I’m going to be offering not so much the secular argument that I want to give, but an outline of the kind of argument that I would want to give and I’m going to dip in on occasion to give you some of the texture of that, some specifics. But believe me, I’m talking about a much bigger project than I’m going to be able to outline right now.

It begins right there in the working title (i.e. “Reasonable Leap”) and I think the title itself is an homage to William Lane Craig’s book ‘Reasonable Faith: Christian Truth and Apologetics’. The book operates as a kind of a master class on Evangelical apologetics by way of presenting the issue of Evangelism in the light of systematic theology. The popularity of ‘Reasonable Faith’ has grown to such an extent that the book has pretty much become one of the standard works of Apologetics in the Evangelical world, often assigned at the undergraduate and graduate level courses in various Bible colleges and seminaries around the English speaking world.

Daniel consumes a steady diet of Christian Apologetics and is an obvious admirer of Craig; I often speculate that Daniel likes to think of himself as the William Lane Craig of Mormonism and I’m confident he has envisioned the posthumous publication of ‘The Reasonable Leap into Light’ as being celebrated enthusiastically by Mormons and eventually becoming a “standard reading” at BYU. So it shouldn’t be surprising then that Daniel follows the Evangelicals in framing the apologetic goal as not establishing the uncontested truth of Christianity (or Mormonism in Daniel’s case), but to demonstrate that those who affirm Christianity (or Mormonism) do so rationally as fallible beings:

Much like a calculating salesman, Daniel wants to push his non-existent, non/ex-Mormon, interlocutors towards accepting the tenets of Mormonism inch by inch until the numbers are simply too good to ignore and you cave. You can’t win unless you play the game, right?Daniel Peterson wrote:...That’s sort of a basic statement of rationality, that if you can’t really decide, you have to just kind of go with one and it’s, you know, as long as it’s roughly 50-50 or 60-40, or something like that, you’re not making an irrational decision. You might turn out to be wrong, but you were reasonable in making that decision..That’s one of the ways I’m going to be looking at rationality. If I can get you to something like 50-50 then I’m relatively happy. You then have to choose based on your own personality, your predilections, your spiritual intuitions and so on. But as I say, in some cases I think I can take the argument further than 50-50..

To help demonstrate this kind of rationality as game theory approach and its value, Daniel introduces his audience to the now infamous Bayes’ theorem of probability. To be perfectly frank about this, I don’t think Daniel was introduced to Bayes’ theorem during the course of his “studies” into either the natural sciences, economics, or philosophy. Rather I’d assert that he was introduced to it via William Lane Craig during a debate with Bart Ehrman about the historical reliability of the New Testament.

I have a copy of Bart Ehrman’s introduction to the New Testament (3rd edition) where he makes a claim to the effect that a practicing Historian of today seeks to establish what “probably” happened in the past and that since supernatural miracles are by definition (according to Ehrman) the least probable of all events, it follows that Historians can’t establish a miracle (i.e. Jesus rising from the dead) as being the most probable course of events. Bart more or less rehearsed this line of reasoning during the debate with Craig.

It was in effect a slow pitch that allowed Craig to smash right out of the park in terms of rebuttal. Craig was able to frame his rebuttal as “Bart’s Blunder” and demonstrate handily that in a Bayesian framework, posterior evidence can be so unique and confirming that it can override any prior epistemic value that is less than 1. Within Bayesian terms, Craig’s point was simply a mathematical inevitability of the algebra involved.

Suffice to say Bart didn’t really have an answer to “Bart’s Blunder” simply due to the fact that was his first time ever encountering Bayes Theorem. I imagine it was Daniel’s first time as well and I bet he was fascinated by the encounter and immediately inuitied how he could use this for his own work:

Now it ought to be an undisputed observation that an argument which sets out to justify a person’s beliefs in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints as rational based on a probability schema derived from the classic axioms of probability is an argument that is fundamentally inductive. Yet when you read the words of Mopologists like Daniel Peterson, Louis Midgley, or Blake Ostler long enough, it becomes an inescapable conclusion that these men are punishingly incompotent when it comes to employing even the most basic concepts of philosophy. As a bulwark against the claim that Daniel’s use of Bayes theorem doesn’t constitute an inductive argument per se I offer this basic definition of induction from a reputable reference work that would find consent not only among empiricists such as John Stuart Mill and David Hume, but also Hans-Georg Gadamer and Sir Karl Popper:Daniel Peterson wrote:This is Bayes’ theorem. Bayes’ theorem is a theorem in probability theory and statistics which describes the probability of an event based on conditions that might be related to the event. I won’t get into the details, but if you have a case where certain things are true, that makes certain other things more likely than not. If you believe there is a God, for example, the probability that Christ rose from the dead rises a bit. If you believe there absolutely is no God and no supernatural then the probability of Christ rising from the dead is very, very low, given your assumptions. In other words, it could become a live or a dead option, depending on what you believed before that. So my case is a cumulative case where I’m trying to argue certain things. Theism first, then Christian theism, then if I’ve got you that far, Mormon Christian theism, OK? And I’m happy with anybody who follows me any distance along the way with those arguments. The further I can get them, the happier I am. But I’m happy if I can get them from atheism to theism, from theism to Christian theism and so on.

Because the ‘Oxford Companion to Philosophy’ contrasts induction with deduction I’d like to pair it with a brief explanation of induction and deduction both from a philosopher named Charles G. Werner. I can find precious little about this man other than he was a colleague of the late Howard Pospesel at the University of Miami in Ohio. To the thousands of philosophy T.A.s that have had to grade piles of formal logic assignments, Pospesel is a familiar name.Oxford Companion to Philosophy wrote:Induction has traditionally been defined as the inference from particular to general. More generally an inductive inference can be characterized as one whose conclusions, while not following deductively from its premisses, is in some way supported by them or rendered plausible in the light of them. Scientific reasoning from observations to theories is often held to be a paradigm of inductive reasoning. (p.405)

I only know that Charles G. Werner existed because he edited a small anthology called ‘Inductive Logic’ I found in a used bookstore in Salt Lake City oddly enough in 2010. It is a cheap paperback published in 1973 by Kendall Hunt publishing company out of Dubuque Iowa. The publishing company is still in business in Dubuque today and it looks like they are still offering the same services they did to Charles Werner, the ability to print and publish custom books cheaply (relatively) for use in the classroom. Outside of this ugly green paperback, the only other words of Werner I’ve laid eyes on comes from a short article he wrote in 1977 for the ‘Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic’.

I always buy these kinds of books when I stumble across them, because I know they were created to serve a certain pedagogical purpose at a certain place at a certain time that simply no longer exists for us. The book has readings from the usual suspects on the topic such as William Whewell, John Stuart Mill, and C.S. Peirce, but also contemporaries like Bertrand Russell and Rudolf Carnap of the Vienna Circle, both of whom had just passed away three years prior to the publication of this little booklet. I wonder if Werner personally knew Carnap when he was at UCLA (Daniel’s alma mater!). Werner also included figures previously unknown to me, such as the English economist W. Stanley Jevons and J.F.W. Herschel. I noticed in Jevons’ Wikipedia entry that under the ‘Legacy’ header there is a quote from ‘The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy and Philosophers’ stating: "Jevons's general view of induction has received a powerful and original formulation in the work of a modern-day philosopher, Professor K. R. Popper." (LOL!) while Herschel originated the use of the Julian day in astronomy and invented blueprints!?! Wikipedia has an absolutely fantastic photographic portrait of Sir Herschel:

My God, Blixa. I’m just rambling to you now. I wrote three paragraphs about some obscure philosopher and embedded a picture from Wikipedia. I’m starting to write like how Daniel Peterson blogs! By the beard of Joseph F. Smith, what is next? Posting clickbait articles from ScienceAlert.com while plagiarizing Robert J. Hutchinson for my cracker barrel column in the Deseret News?! See you were wrong Blessed Blixa, visiting Reverend Kishkumen wouldn’t just do me some good, I actually think I might be in dire need of his ministrations. I need to continue.

So Werner (following C.S. Peirce) divides logical inferences into two broad categories: Deductive and Inductive. He indicates that Deduction can be characterized as “Explicative/Analytic” and Induction can be characterized as “Amplifiative/Synthetic”. Werner then defines those terms as follows (bolding mine):

Charles G. Werner wrote:Analytic inference: [T]he conclusion follows necessarily from the premises, i.e., it is not logically possible—it is self-contradictory—for the premise to be true and the conclusion to be false.

Explicative inference: [T]he conclusion makes explicit what was contained implicitly in the premises.

Synthetic inference: [T]he conclusion does not follow necessarily from the premises, i.e., it is logically possible—it is not self-contradictory— for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false.

Amplifiative inference: [T]he conclusion adds something to what is contained in the premises. (p.2)

So Daniel is working on a book length inductive argument laying out a positive case for his deeply held beliefs, that isn’t any different in principle from what Richard Swinburne did in his book ‘The Existence of God’. Why give this good man and scholar all this guff and libel and not hand the same treatment to Swinburne? I suppose I would if Swinburne had written the things Daniel has written. The real difference is that Swinburne is actually a competent philosopher with numerous contributions to the Philosophy of Science, so if I can pretend that Daniel has expended any meaningful effort reading any sort of philosophy text then I can easily assume the same about Richard without a nanosecond of hesitation.

What are some of those things Daniel has written? Once again I take us back to review ‘Can the Study of History Yield Genuine Knowledge’. I know I’ve quoted it before, but I see no harm in quoting it again. I see no problem going back to the same well again and again to make my points. Repetition is not a sign sloth.

Anyways Daniel says:

Daniel then goes on to make two characterizations; one each about the natural sciences and the modern discipline of history respectively. He deals with the natural sciences first (bolding mine):Daniel Peterson wrote:I offer, below, a comment on the subject from the great German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900-2002; yes, you read that right). It’s perhaps just a bit difficult, but his point seems to me unassailably sound to the point of obviousness.

This statement incorrectly represents Gadamer’s position, because generalizing rules from particular cases doesn’t exhaust what induction is and also does not exhaust the activity of science. (If you agree with Popper, then induction doesn’t have much bearing on the practice of science whatsoever). I think this is easily demonstrated by both the ‘Oxford Companion to Philosophy’ and from Werner’s introduction to the anthology ‘Inductive Logic’.Daniel Peterson wrote:The physical and natural sciences study particular cases in order to generalize rules from those particular cases...

Yet my bulwark might still fail and a Mopologist reading this might object to my sources and reject my assertions that Gadamer would agree with them. Could I demonstrate that Gadamer believed similarly to my sources from the text of ‘Truth and Method’? Sure and I’ll do you one better. I’ll do it only using the section we’ve covered in this email. Consider the opening paragraph of ‘Truth and Method’ where Gadamer begins to establish the influence of John Stuart Mill:

The reference “Mill’s Logic” is referring to Mill’s influential work on induction titled in English as ‘A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive’. Mill’s influence on German intellectual culture is a consistent theme in the section ‘The Problem of Method’ in Gadamer’s book. Mill’s work on induction shaped how 19th century German scholars and scientists understood their own disciplines in both the natural sciences and the humanities. As we saw for ourselves, Gadamer goes to some length to reinforce that.Gadamer wrote:The logical self-reflection that accompanied the development of the human sciences in the nineteenth century is wholly governed by the model of the natural sciences. A glance at the history of the word Geisteswissenschaften shows this, although only in its plural form does this word acquire the meaning familiar to us. The human sciences (Geisteswissenschaften) so obviously understand themselves by analogy to the natural sciences that the idealistic echo implied in the idea of Geist (“spirit”) and of a science of Geist fades into the background. The word Geisteswissenschaften was made popular chiefly by the translator of John Stuart Mill’s ‘Logic’. In the supplement to his work Mill seeks to outline the possibilities of applying inductive logic to the “moral sciences.” The translator calls these Geisteswissenschaften. Even in the context of Mill’s ‘Logic’ it is apparent that there is no question of acknowledging that the human sciences have their own logic but, on the contrary, of showing that the inductive method, basic to all experimental science, is the only method valid in this field too. (p.3)

Did John Stuart Mill understand induction as only being the activity of generating universal statements based on a certain number of particular statements? Thankfully for me, Werner’s ‘Inductive Logic’ includes the relevant passages from Mill’s ‘A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive’:

Interesting that Mill thinks even acquiring individual facts is part and parcel of induction.John Stuart Mill wrote:For the purpose of the present inquiry, Induction may be defined, the operation of discovering and proving general propositions. It is true that (as already shown) the process of indirectly ascertaining individual facts, is as truly inductive as that by which we establish general truths. (p.34)

For Mill, induction punctuates everyday lifeJohn Stuart Mill wrote:But it is not a different kind of induction; it is another form of the very same process: since, on the one hand, generals are but collections of particulars, definite in kind but indefinite in number; and on the other hand, whenever the evidence which we derive from observation of of known cases justifies us in drawing an inference respecting even one unknown case, we should on the same evidence be justified in drawing a similar inference with respect to a whole class of cases. (p.34)

And Gadamer himself mentions that Helmholtz tries to articulate these other kinds of induction that make up the human experience from which the humanities (i.e. the human sciences) draw their conclusions:John Stuart Mill wrote:If these remarks are just; if the principles and rules of inference are the same whether we infer general propositions or individual facts; it follows that a complete logic of the sciences would be also a complete logic of practical business and common life...Whether we are inquiring into a scientific principle or into an individual fact, and whether we proceed by experiment or by ratiocination, every step in the train of inferences is essential inductive, and the legitimacy of the induction depends in both cases upon the same conditions. (p.34-35).

Look here how Daniel then goes on to describe what historians do in contrast to scientists:Gadamer wrote:Helmholtz distinguished between two kinds of induction: logical and artistic-instinctive induction. That means, however, that his distinction was basically not logical but psychological. Both kinds of science make use of the inductive conclusion, but the human sciences arrive at their conclusions by an unconscious process. Hence the practice of induction in the human sciences is tied to particular psychological conditions. (p.5)

That fool thought from his skimming of one paragraph that Gadamer’s use of induction was falsely equivalent with scientists who “study particular cases in order to generalize rules from those particular cases” and then tries to portray the discipline of history not doing this at all.Daniel Peterson wrote:By contrast, historians can spend, and have spent, entire careers on the life and times of Andrew Jackson, on the late Byzantine empire, on the Umayyad Dynasty, on the biography of Napoleon, and on the Tokugawa shogunate. And they’ve done so not so much in order to formulate predictive general theories — in the style of biochemistry or particle physics — about the American presidency, the rise of dynasties or the collapse of states, or the life-cycle of famous Corsicans, as because they wanted to understand those people or those periods in and of themselves.

Just consulting the books that just happen to be within my reach, dearest Blixa, I can find numerous counterexamples to this. I can think of no less a historian than E.G. Turner himself, the revered papyrologist and master classicist, and his delightful tome ‘Greek Manuscripts of the Ancient World’:

What Turner describes above falls neatly into the category of induction as laid out by John Stuart Mill, and fits seamlessly into how Gadamer uses induction, while at the same time conforming to the definition provided by the ‘Oxford Companion to Philosophy’ and Werner’s anthology ‘Inductive Logic’.Eric Gardner Turner wrote:In these continuous blocks of writing we shall also find that the letter which metrical laws require to be elided are often written out in full (scriptio plena). It is the reader’s task, knowing the rules, to read these lines metrically (a duty we still accept in the reading of Latin). The presence of these eligible letters in prose texts does not mean that the author or scribe tolerated hiatus. A single scribe’s practice will often vary: sometimes he will write in scriptio plena, sometimes use tacit elision. From ii B.C. onwards the separating apostrophe...comes into occasional use to mark such elisions; or the corrector may go through the text marking by an expunging dot or a cancel stroke those vowels which cause hiatus. (p.9)

Daniel grasps the basics of Gadamer’s point: the natural sciences and the humanities are different. From there he stumbles into a mistake about what Gadamer was writing about, the natural sciences and the humanities are not different because the natural sciences only seek to establish regularities and historians don’t, nor are they different because the natural sciences use induction and the humanities don’t. In actuality, the natural sciences and humanities differ because one uses methods and ought to and the other uses methods and ought not to.

Look at this disaster of an e-mail Blixa, see how the study of Mopologetics is often like the study of an onion? You consistently have to peel away layer after layer of mistakes as if there was no termination of layers, but the mistakes are just hideously stupid and made out of a careless disregard for any notion of honesty or care for a broader truth. Peel away at the onion of Mopologetics long enough Blixa and soon you will find yourself weeping.

Since I mentioned Richard Swinburne, does this unflattering photo of him not scream Religious Education at BYU?

-

_MrStakhanovite

- _Emeritus

- Posts: 5269

- Joined: Tue Apr 20, 2010 3:32 am

Re: Tales From The Reverend’s Office: Why Won’t Daniel Peterson STFU?

I apologize for not responding to people in this thread, but I find that if I spend time on the board it takes away from the efforts trying to finish these little projects I start.

-

_Doctor Scratch

- _Emeritus

- Posts: 8025

- Joined: Sat Apr 18, 2009 4:44 pm

Re: Tales From The Reverend’s Office: Why Won’t Daniel Peterson STFU?

Mr. Stak--

You'll have to forgive me. The Dean had ordered me to attend 6 different conferences around the globe. I was very much opposed to doing this on account of the pandemic, but, you know, duty calls, I guess. I forewent a vacation due the pandemic, and yet I feel that even in my job duties, I'm needlessly endangering other people. As the old saying goes: the Dean has his reasons.

That being said, did you see this?:

You'll have to forgive me. The Dean had ordered me to attend 6 different conferences around the globe. I was very much opposed to doing this on account of the pandemic, but, you know, duty calls, I guess. I forewent a vacation due the pandemic, and yet I feel that even in my job duties, I'm needlessly endangering other people. As the old saying goes: the Dean has his reasons.

That being said, did you see this?:

Gemli wrote:You must think I live a cloistered life where such reading materials are unavailable. I can assure you I've read and studied NDEs. It would take extremely convincing evidence to imagine that they were peeks into the netherworld, given that the reports are the only evidence, and the reports are created by diseased or drugged brains. Normal brains produce ordinary dreams that are equally bizarre, but we don't take those to have netherworld connections. There are drugs and certain mental states that mimic NDEs very closely. To assume a spiritual cause would be an extreme overreaction to the available evidence, a "red shoe" on a ledge notwithstanding.

Ha ha ha ha!Daniel Peterson wrote:gemli: "You must think I live a cloistered life where such reading materials are unavailable."

Not at all. They're available. You have no excuse for not having studied them while still presuming to pontificate on the subject.

"[I]f, while hoping that everybody else will be honest and so forth, I can personally prosper through unethical and immoral acts without being detected and without risk, why should I not?." --Daniel Peterson, 6/4/14

-

_MrStakhanovite

- _Emeritus

- Posts: 5269

- Joined: Tue Apr 20, 2010 3:32 am

Re: Tales From The Reverend’s Office: Why Won’t Daniel Peterson STFU?

Part 2(h): Epistle to The North African

We have a good working idea of what induction is now. We know the meta-argument used in ‘The Reasonable Leap into Light: A Barebones Secular Argument for the Gospel’ is Bayesian and thus inductive. Does Daniel make a historical argument along inductive lines? Lets pick up Daniel’s argument further down the line to find out:

-Jewish critics of the Early Christian acknowledge the tomb of Jesus was empty.

-1 Corinthians 15 is a very early list of actual witnesses.

-The earliest portions of the New Testament are creeds where the Resurrection is central to the faith.

-The behaviour of the Apostles and other early believers is consistent with them holding authentic beliefs about the risen Christ.

Daniel’s point is to ultimately ask the question "what do all these facts point to?" In the spirit of the ‘Oxford Companion to Philosophy’ it is that the conclusion that Jesus Christ actually rose from the dead is rendered quite plausible by the articulation of these points of evidence. Taken individually, none of these data points really entails the resurrection, but if they are arrayed together they do make it plausible (according to Daniel at least). A nice inductive argument made from ancient history. What did Gadamer say about induction in relation to the humanities in ‘Truth and Method’?

Keep the above in mind because I want to swing around and go back to Popper’s ‘The Logic of Scientific Discovery’ and continue his discussion of induction:

In modern logic (another area of study Daniel Peterson knows precious little) there are two primary ways of assessing an argument: by syntax or semantics. Much of modern logic and pure mathematics is dedicated to the analysis of syntax, are these strings of symbols constructed the right way? Does this string of symbols hold the correct relationship to this other string of symbols such that we can properly deduce this third string of symbols? What this means is that formal logical languages are often devoid of semantic content (which is why variables are used) and since the focus is on syntactic relations, the strings of symbols are often meaningless to the people manipulating them because the focus is elsewhere. Hence the joke, no one knows what these statements mean because we’ve assigned no semantic content to them.

How does that relate to Popper. Well at the graduate level of logic, instructors like to drive home Russell’s point by including a certain problem on a quiz or homework assignment. The students are asked to prove a conclusion, which is like 95% of all homework and tests in modern logic, so nothing will strike these students as being different. Later it is revealed that those who were able to correctly do the derivations had just deduced Balmer’s formula for the emission spectra for gasses logically from Bohr’s theory on the hydrogen atom, without even knowing they were doing so.

But of course this kind of deductivism has a level of arbitrariness that is, and ought to be, uncomfortable for anyone interested in the philosophy of science. Popper has to deal with a slew of objections to his brand of deductivism and one of the more pressing objections is known as the problem of demarcation:

All the more better is if that book has been cited explicitly by Daniel Peterson on his blog:

Oh! There goes my alarm, I have to stop and start my way towards Reverend’s office. Once again I must apologize for the length and rambling nature of this e-mail. Thank you for humoring me in my time of need!

Yours,

Alfonsy Stakhanovite.

We have a good working idea of what induction is now. We know the meta-argument used in ‘The Reasonable Leap into Light: A Barebones Secular Argument for the Gospel’ is Bayesian and thus inductive. Does Daniel make a historical argument along inductive lines? Lets pick up Daniel’s argument further down the line to find out:

To Daniel’s credit he begins to succinctly summarize those arguments in a short amount of time. For the failed sake of brevity, I’ll provide my outline of his summary.Daniel Peterson wrote:But now if we’ve established it’s at least possible, you know, that the universe is some sort of more mysterious place than we’d thought, then the whole idea of the resurrection of Christ becomes at least something you can be open to. So what is the evidence for that? Did Christ really rise from the dead?

Well, there are a lot of detailed historical arguments that can be made for this...

-Jewish critics of the Early Christian acknowledge the tomb of Jesus was empty.

-1 Corinthians 15 is a very early list of actual witnesses.

-The earliest portions of the New Testament are creeds where the Resurrection is central to the faith.

-The behaviour of the Apostles and other early believers is consistent with them holding authentic beliefs about the risen Christ.

Daniel’s point is to ultimately ask the question "what do all these facts point to?" In the spirit of the ‘Oxford Companion to Philosophy’ it is that the conclusion that Jesus Christ actually rose from the dead is rendered quite plausible by the articulation of these points of evidence. Taken individually, none of these data points really entails the resurrection, but if they are arrayed together they do make it plausible (according to Daniel at least). A nice inductive argument made from ancient history. What did Gadamer say about induction in relation to the humanities in ‘Truth and Method’?

It seems to me that Gadamer is actually quite hostile to Daniel’s apologetic efforts. Karl Popper is probably even more so. This can brought out by what Daniel says below:Gadamer wrote:However strongly Dilthey defended the epistemological independence of the human sciences, what is called “method” in modern science remains the same everywhere and is only displayed in an especially exemplary form in the natural sciences. The human sciences have no method of their own. Yet one might well ask, with Helmholtz, to what extent method is significant in this case and whether the other logical presuppositions of the human sciences are not perhaps far more important than inductive logic. (p.7)

Remember a the outset of this talk, Daniel’s ‘Summa Mopologetica’ is “going to argue that you can prove religious claims true or specifically Latter-day Saint claims true” but rather “argue that they’re reasonable” and in the odd case “get pretty strong security”.Daniel Peterson wrote:OK, so again, remember, we’re thinking in Bayesian terms, and ... let’s see how much time I have here now. Oh my, it’s getting tight. I’ll go through this very quickly to outline the logic of the last part. I have 51 seconds by my watch.

OK, well, suppose that I’ve gotten you this far. You’ve said, “OK, I’m willing to entertain the possibility that theism is true. There might be a God. This universe may not be the naturalistic, closed system that I thought it was. Maybe even Jesus rose from the dead. I mean, it’s at least a ... it’s a possibility to consider.” That’s N.T. Wright’s conclusion, that, as a historian, he says, the only explanation I can come up with to account for the data is that certainly the apostles thought Jesus rose from the dead.

Keep the above in mind because I want to swing around and go back to Popper’s ‘The Logic of Scientific Discovery’ and continue his discussion of induction:

Popper flat out states that induction lacks logical justification; that there is no logical way one can move from a potentially infinite number of individual cases of swans being white to a universal statement that all swans are white. This is what motivates Popper in flat out discarding the strategy that if we study and refine inductive methods, we’ll stumble upon something that will enable inductive methods to guarantee the truths of its conclusions in some manner similar to deductive methods.Popper wrote:Now it is far from obvious, from a logical point of view, that we are justified in inferring universal statements from singular ones, no matter how numerous; for any conclusion drawn in this way may always turn out to be false: no matter how many instances of white swans we may observed, this does not justify the conclusion that all swans are white. (p.4)

What Popper is taking aim at is a philosophical doctrine known as “logical probabilism” made famous by the economist John Maynard Keynes in his work ‘A Treatise on Probability’. The doctrine holds that the relationship between uncertain evidence and conclusions based on that evidence is one of pure logic. This has implications for Daniel, because his entire apologetic project is dedicated to making Mormons plausible through a probabilistic schema. What Popper offers for replacement is interesting:Popper wrote:My own view is that the various difficulties of inductive logic here sketched are insurmountable. So also, I fear, are those inherent in the doctrine, so widely current today, that inductive inference, although not ‘strictly valid’, can attain some degree of ‘reliability’ or of ‘probability’. According to this doctrine, inductive inferences are ‘probable inferences’. (p.6)

What Popper advocates is a species of “deductivism”; in the philosophy mathematics deductivism held that pure mathematics is really just investigating deductive consequences of arbitrarily chosen axioms expressed in a formal language. Bertrand Russell (who was friendly to deductivism) used to joke that logicians and mathematicians never knew what they were talking about, yet still loved to get together and talk. Now Russell didn’t mean logicians and mathematicians just sat around bullshiting eachother, really the joke was about syntax.Popper wrote:According to the view that will be put forward here, the method of critically testing theories, and selecting them according to the results of tests, always proceeds on the following lines. From a new idea, put up tentatively, and not yet justified in any way—an anticipation, a hypothesis, a theoretical system, or what you will—conclusions are drawn by means of logical deduction. These conclusions are then compared with one another and with other relevant statements, so as to find what logical relations (such as equivalence, derivability, compatibility, or incompatibility) exist between them.(p.9)

In modern logic (another area of study Daniel Peterson knows precious little) there are two primary ways of assessing an argument: by syntax or semantics. Much of modern logic and pure mathematics is dedicated to the analysis of syntax, are these strings of symbols constructed the right way? Does this string of symbols hold the correct relationship to this other string of symbols such that we can properly deduce this third string of symbols? What this means is that formal logical languages are often devoid of semantic content (which is why variables are used) and since the focus is on syntactic relations, the strings of symbols are often meaningless to the people manipulating them because the focus is elsewhere. Hence the joke, no one knows what these statements mean because we’ve assigned no semantic content to them.

How does that relate to Popper. Well at the graduate level of logic, instructors like to drive home Russell’s point by including a certain problem on a quiz or homework assignment. The students are asked to prove a conclusion, which is like 95% of all homework and tests in modern logic, so nothing will strike these students as being different. Later it is revealed that those who were able to correctly do the derivations had just deduced Balmer’s formula for the emission spectra for gasses logically from Bohr’s theory on the hydrogen atom, without even knowing they were doing so.

But of course this kind of deductivism has a level of arbitrariness that is, and ought to be, uncomfortable for anyone interested in the philosophy of science. Popper has to deal with a slew of objections to his brand of deductivism and one of the more pressing objections is known as the problem of demarcation:

The ability to distinguish legitimate science like organic chemistry from an illegitimate science like homeopathy is incredibly important today, even more so than in Popper’s own. For Popper, those who advocate for some kind of induction mistake verification as being the lynchpin for solving the demarcation between science and non-science are making a mistake. Experience and experimentation cannot do this via verification, but falsification can:Popper wrote:Of the many objections which are likely to be raised against the view here advanced, the most serious is perhaps the following. In rejecting the method of induction, it may be said, I deprive empirical science of what appears to be its most important characteristic; and this means that I remove the barriers which separate science from metaphysical speculation. My reply to this objection is that my main reason for rejecting inductive logic is precisely that it does not provide a suitable distinguishing mark of the empirical, non-metaphysical, character of a theoretical system; or in other words, that it does not provide a suitable ‘criterion of demarcation’.

The problem of finding a criterion which would enable us to distinguish between the empirical sciences on the one hand, and mathematics and logic as well as ‘metaphysical’ systems on the other, I call the problem of demarcation. (p.10-11)

Of course Popper isn’t launching an attack on empiricism and would insist that his views are being more faithful to that view of epistemology:Popper wrote:Thus inference to theories, from singular statements which are ‘verified by experience’ (whatever that may mean), is logically inadmissible. Theories are, therefore, never empirically verifiable. If we wish to avoid the positivist’s mistake of eliminating, by our criterion of demarcation, the theoretical systems of natural science, then we must choose a criterion which allows us to admit to the domain of empirical science even statements which cannot be verified.

But I shall certainly admit a system as empirical or scientific only if it is capable of being tested by experience. These considerations suggest that not the verifiability but the falsifiability of a system is to be taken as a criterion of demarcation. In other words: I shall not require of a scientific system that it shall be capable of being singled out, once and for all, in a positive sense; but I shall require that its logical form shall be such that it can be singled out, by means of empirical tests, in a negative sense: it must be possible for an empirical scientific system to be refuted by experience. (p.18)

Now when it comes to a notion of probability and why Popper thinks such methods cannot save induction from his criticism, there is a lot of material to pick from. He has an entire chapter dedicated to the topic that spans from page 133 to 209, plus numerous appendices devoted to different aspects of probability. However I’d like to draw my final Popper quotation not from ‘The Logic of Scientific Discovery’ but from another book made up of materials much later in Popper’s career.Popper wrote:The proposed criterion of demarcation also leads us to a solution of Hume’s problem of induction—of the problem of the validity of natural laws. The root of this problem is the apparent contradiction between what may be called ‘the fundamental thesis of empiricism’—the thesis that experience alone can decide upon the truth or falsity of scientific statements—and Hume’s realization of the inadmissibility of inductive arguments. This contradiction arises only if it is assumed that all empirical scientific statements must be ‘conclusively decidable’, i.e. that their verification and their falsification must both in principle be possible. If we renounce this requirement and admit as empirical also states which are decidable in one sense only—unilaterally decidable and, more especially, falsifiable—and which may be tested by systematic attempts to falsify them, the contradiction disappears: the method of falsification presupposes no inductive inference, but only the tautological transformations of deductive logic whose validity is not in dispute. (p.20)

All the more better is if that book has been cited explicitly by Daniel Peterson on his blog:

Let us see what Sir Karl Popper also wrote in ‘Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge’:Daniel Peterson wrote:“It is a disturbing fact,” wrote Sir Karl Popper, “that even an abstract study like pure epistemology is not as pure as one might think (and as Aristotle believed) but that its ideas may, to a large extent, be motivated and unconsciously inspired by political hopes and by Utopian dreams” (Karl R. Popper, Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge [London: Routledge; Kegan Paul, 1969], 6).

I think it is safe to say that Karl Popper’s view of science is totally hostile to that of Daniel’s, but not nearly as hostile as Gadamer’s view of history is to Daniel’s.Karl Popper wrote:Like many other philosophers I am at times inclined to classify philosophers as belonging to two main groups—those with whom I disagree, and those who agree with me. I also call them verificationists or the justificationist philosophers of knowledge (or of belief), and the falsificationists or fallibilists or critical philosophers of knowledge (or of conjectures). I may mention in passing a third group with whom I disagree. They may be called the disappointed justificationists—the irrationalists and sceptics.

The members of the first group—the verificationists or justificationists—say, roughly speaking, that whatever cannot be supported by positive reasons is unworthy of being believed, or even being taken into serious consideration.

On the other hand, the members of the second group—the falsificationists or fallibilists—say, roughly speaking, that what cannot (at present) in principle be overthrown by criticism is (at present) unworthy of being seriously considered; while what can in principle be so overthrown and yet resists all our critical efforts to do so may quite possible be false, but is at any rate no unworthy of being seriously considered and perhaps even of being believed—though only tentatively.

Verificationists, I admit, are eager to uphold that most important tradition of rationalism—the fight of reason against superstition and arbitrary authority. For they demand that we should accept a belief only if it can be justified by positive evidence; that is to say, shown to be true, or, at least, to be highly probable. In other words, they demand that we should accept a belief only if it can be verified, or probabilistically confirmed.

Falsificationists (the group of fallibilists to which I belong) believe—as most irrationalists also believe—that they have discovered logical arguments which show that th programme of the first group cannot be carried out: that we can never give positive reasons which justify the belief that a theory is true. But, unlike irrationalists, we falsificationists believe that we have also discovered a way to realize the old ideal of distinguishing rational science from various forms of superstition, in spite of the breakdown of the original inductivist or justificationist programme. We hold that this ideal can be realized, very simply, by recognizing that the rationality of science lies not in its habit of appealing to empirical evidence in support of its dogmas—astrologers do so too—but solely in the critical approach—in an attitude which, of course, involves the critical use, among other arguments, of empirical evidence (especially in refutations). For us, therefore, science has nothing to do with the quest for certainty or probability, or reliability. (p.228-229)

Oh! There goes my alarm, I have to stop and start my way towards Reverend’s office. Once again I must apologize for the length and rambling nature of this e-mail. Thank you for humoring me in my time of need!

Yours,

Alfonsy Stakhanovite.